Tonight, I go on my fifth annual road trip with a few high school friends. The six of us

met in seventh and eighth grade making films. Now and for the past four years we’ve been going in separate places: different schools, different interests, different cities–even states.

Still, something has held us together, for the past eight years. Sometimes, that’s hard to believe.

Dunbar’s number dictates we can only keep track of around 150 beings at any given time. If they’re too distant, they don’t make the cut and blur behind a thin haze of anonymity.

During our lives, few people make the cut. Those who do so consistently become friends.

Friendship has the rare honor of being part of “the human condition,” the seemingly universal and timeless experience that defines what it means to be human. I don’t know if anyone has ever tried to outline our condition, but I imagine that friendship would be on the list somewhere.

Despite it’s prevalence, however, friendship remains a brittle obscure topic. As Thoreau opens in his essay Friendship, “Friendship is evanescent in every man’s experience, and remembered like neat lightening in past summers.” It takes place for all of us, sometimes for just a fragile collection of moments. Yet we can barely describe what makes it so essential.

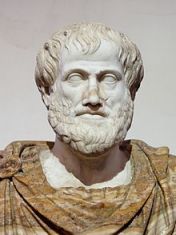

In philosophy, the most famous attempt to outline friendship is probably Aristotle’s. He argues that three main kinds of friends exist: utility, pleasure, and virtue. Friends of utility fulfill a certain role, like a coworker or even a clerk at your favorite store. We know them, say hello, and ask how they are, but for the most part, conversations are flat and brief. We would never tell them our beloved puppy Atticus just drowned, and we don’t actively seek their company.

We do seek the company of friends of pleasure. They’re fun. They make us laugh, tell good stories, understand inside jokes, and may even give us a mischievous glance over the shoulder of someone who barges into our conversation.

According to Aristotle, most “friends” fall into these categories. A few go farther.

Friends of virtue are the true, time-tested friends who contain that special, silent quality that instantly bonds you together and inspires trust. Also, in Aristotle’s view, they make you more “virtuous.”

The word virtue now sounds a bit antiquated and prudish. To me, it conjures images of a 17th century gentleman, replete with frills and powdered wig, laying down a coat to allow a lady to cross a muddy road, as he stands with prim attention beside her, maybe offering an elbow.

But the word “virtue” has a much deeper root. It comes from the Latin word “vir,” meaning “man.” In the charmingly sexist past, a “virtuous” person had all the qualities of a good man: strength, courage, perseverance, a sound moral code, intelligence, etc.

Thus, “virtue friends” make us better people,

Many big names after Aristotle wrote about friendship: Seneca, Cicero, Kant, Francis Bacon, Thoreau, Emerson, Nietzsche, and countless others.

Cicero and Seneca largely echoed Aristotle’s classical ideal. Kant filtered friendship through his categorical imperative, stressing the need to treat friends as rational, independent ends in themselves. Francis bacon discussed the “fruits of friendship,” chiefly noting a friend’s ability to give us “faithful counsel.” Emerson wisely wrote, “the

only way to have a friend is to be one.” And Nietzsche thought friends should challenge us, a bit like running partners.

Men weren’t the only people to talk about friendship.

It’s a woman’s thing, too. Must of us would nod in approval when Emily Dickinson said, “My friends are my estate.” And Anaïs Nin’s journals have a beautiful view: “Each friend represents a world in us, a world not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.”

My own small foray into friendship does not have the clarity of Aristotle’s categories or the poetry of Anaïs’ quote. I’m still a rookie. Still, I think modern America’s view of friendship has grown flimsy. We use the word “friend” to refer to old classmates, drinking buddies, or deep, personal connections.

Sometimes, this gets confusing. We consider someone a “friend,” but then they do or say something that violates our trust, shirks our definition, and leaves us lost, wondering who our friends really are.

Moreover, I don’t know what Emerson would say about Facebook friends, but I doubt he’d call the such friend’s the “masterpiece of nature,” as he wrote in “Friendship.”

One philosopher spoke at my last school about Aristotle’s categories of friendships in the cyber age: our connections on social media crowd out virtue friends with friends of utility and pleasure. Moreover, people from our past, like ex-girlfriends or old classmates, crop up and reconnect. Ordinarily these friendships would have faded, following their natural course. Now, they don’t. Instead, they vie with current relationships.

I think a little clarity would help. Like most philosophy, different views on friendship often leave more questions than conclusions. But they force us to think. Who are our friends? What does friendship really mean?

One star-strewn night, as I stood looking up at the sky with one of my closest friends, a feeling hit me: a mingling of absolute trust and respect–a sense that I could act with this person the same way I do alone. I didn’t need my public face. And I somehow knew that even if time changed us and separated us, I would cherish this moment and this person, even in anger. Something connected us, deeper and more longterm than normal thoughts and feelings could truly capture. I felt like our friendship was way beyond us.

Perhaps that’s a “friend.” I don’t know. Still, I can relate to Thoreau’s beautiful entry in his journals about friendship. As he concludes, “Friendship is the fruit which the year should bear; it lends its fragrance to the flowers.”

It is part of the human condition, and in my opinion, it may be the most beautiful part, however little we truly understand it.

I find, as I get older, the need to connect with friends diminishes a great deal, although not necessarily the need to have and keep them, though far fewer. I wonder if it’s just me, or if this is common; I suspect it is. Certainly the boon companionship of late night taverneering goes by the wayside!

Pingback: Cryptoquote Spoiler – 07/14/13 | Unclerave's Wordy Weblog

Great post, and as you mention there is so much to friendship it is hard to categorize. They certainly are like a running partner, giving us the challenge to reach our potentials, and the great ones are like family to catch us when we do fail (especially on those late nights of ‘taverneering’ Mikels mentions above!),

nice

Thanks! And thanks for coming by and taking the time to comment.

I am thinking that someone who I would be attracted to in friendship would be someone who possesses a certain combination of both those attributes that I possess myself that I feel are important and those attributes that I aspire to and/or admire but perhaps do not possess.

I agree. I also think a true, deep friend is someone who possesses a certain brokenness and vulnerability that allows you to be honest in hard times while maintaining respect.